We all know that information is passed down from one generation to the next through genes. But what about another type of non-gene change in your DNA, called epigenetics?

Literally meaning “above the genes”, epigenetic changes are chemical modifications to your DNA that act as “on/off” switches for genes, changing gene expression without altering the gene’s code directly. A gene is turned “off” when a modification is attached and turned back “on” when the modification is removed. The most widely discussed modification is DNA methylation, where a small methyl group (CH3) is added to DNA.

Epigenetic changes are reversible and can be readily altered by the environment. The record of epigenetic changes throughout your genome is called your epigenome. Importantly, the epigenome can be passed down throughout generations, affecting children’s traits by altering gene expression without changing the DNA code.

Although your health depends on the genes and epigenome you were born with, you still have control over the effects from your lifestyle. So how do your activities and lifestyle choices affect your epigenome and how do those changes impact future generations?

Epigenetics and its relation to health

Everything you do affects your epigenome, from your environment and sleeping habits to diet and exercise. Epigenetics also plays an important role in disease, especially cancers, so understanding how to alter the epigenome is important.

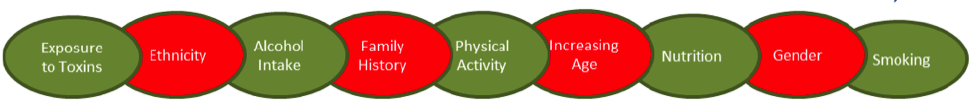

Many aspects can affect epigenetic modifications, including those you can (green) and can’t (red) change.

Source: Nutrients. 2015. 7(2): 922-947.

Compounds in certain foods are thought to protect against cancer by influencing epigenetic modifications. Increased methylation of certain DNA regions, called gene promoters, turns genes “off”.

The omega 3 fatty acids EPA and DHA (found in fish oil) are anti-inflammatory because they turn “off” the expression of an inflammatory enzyme (COX-2) through methylation of its promoter. Polyphenols (found in green tea, coffee, red wine, fruits, and vegetables) are known to turn “on” certain genes by direct demethylation or inhibition of methylation enzymes. Folate (found in dark leafy greens or taken as a supplement) is converted into an important methyl donor, which can then methylate DNA. Folate intake is linked to higher methylation of a specific growth factor gene (IGF2), which turns “off” the growth factor and can help prevent cancer, such as colorectal cancer.

However, not all dietary choices cause positive epigenetic effects. Alcohol consumption has been linked to harmful epigenetic changes and several cancers. Various genes were turned “off” via increased promoter methylation in colorectal cancer patients who drank heavily versus those who drank little to no alcohol. Genes involved in two regulatory pathways (MGMT and WNT) were turned “off” via increased promoter methylation in head and neck cancer patients who drank versus nondrinkers.

While exercise is known for its multitude of beneficial health effects, it has also been linked to altering DNA methylation.

Six months of aerobic exercise caused DNA methylation changes in muscle and fat tissues, which directly affected fat creation and storage. Exercise in sedentary young people showed reduced methylation in a leg muscle (vastus lateralis) at certain promoters of genes involved in metabolism (PGC-1α, PDK4, and PPAR-δ), which beneficially increased metabolism.

The epigenetic effects of working out was studied in 23 healthy young adults. Over three months, the participants exercised one leg by bicycling while resting the other leg, each participant acting as their own control. Both increased or decreased methylation was seen in over 5,000 places on the genome of leg muscle cells upon exercise. Most of the affected genes were involved in inflammation, energy metabolism, and insulin response with the epigenetic changes resulting in healthier muscles.

Altered DNA methylation is commonly seen in cancer. Exercise was suggested to provide protective anti-cancer effects by turning “on” tumor suppressor genes through decreasing methylation. However, the complexity of measuring self-reported exercise from small groups of people and having differing results from various studies doesn’t allow for more solid conclusions to be made.

What you choose for your own lifestyle will only partially influence your epigenome – some modifications may have been added before you were born.

Epigenetic inheritance

Your epigenome isn’t entirely your own – you’ve inherited some epigenetic markers from your parents, grandparents, and beyond. This means that your ancestors’ lifestyles and experiences have affected your epigenome and you will, in turn, shape your children’s epigenome.

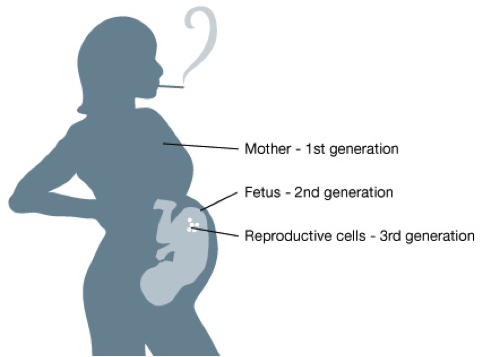

Epigenetic changes can be hereditary, being passed down through the generations. When a woman is pregnant, three generations are directly affected by her lifestyle: 1) herself, 2) her child, and 3) her grandchildren (by way of her child’s eggs or sperm).

A pregnant mother’s lifestyle and environment can directly affect three generations simultaneously. Source: learn.genetics.utah.edu

Epigenetics is particularly important during two key periods: “critical windows” in early development, and “dietary transitions” in adults, such as chronic over eating, a high fat diet, or chronic caloric restriction.

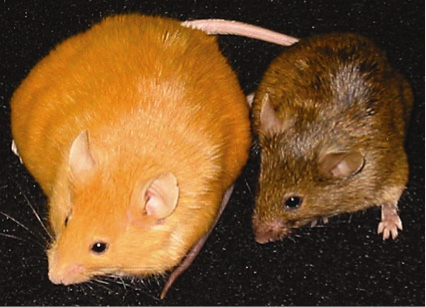

Maternal nutrition has been linked to epigenetic changes in their children. Diet alone was used to influence the appearance, longevity, and disease susceptibility of mice. Pregnant agouti mice, known for their golden coats, obesity, and higher susceptibility to cancer and diabetes, were fed foods rich in methyl donors, such as onions, garlic, and beets. Although the harmful agouti gene was passed down from mother to baby, increased methylation of the gene from the methyl-rich diet turned “off” the gene, producing babies that were brown, slender, lived longer, and were less susceptible to cancer and diabetes. Supplementing maternal nutrition with methyl donors such as folate, originally intended to prevent brain and spine defects, may also alter epigenetic gene regulation during embryo development.

A diet rich in methyl donors (folate, choline, and vitamin B12) consumed during pregnancy turned “off” a harmful gene passed on from the mother (yellow, left) to baby (brown, right). Source: discovermagazine.com

Although regular moderate exercise during pregnancy is believed to be beneficial to both the mother and child, there is little research on the epigenetic changes induced by maternal exercise. Better cardiovascular health (decreased fetal heart rate and increased stroke volume) was seen in babies at 36 weeks of gestation in pregnant women who exercise regularly. Mice born to mothers who ran on a wheel voluntarily had increased neuron creation in a specific part of the brain (the hippocampus). Improved sugar regulation and insulin sensitivity were seen in baby rats whose mothers ran on a wheel voluntarily before conception and during the mating period. Maternal exercise can also even lower the risk for developing diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disease in their children as adults.

Can you learn about your epigenome through DNA testing?

Genetic testing can reveal what genes you carry and how they affect your health and traits, but they don’t tell you anything about your epigenome. Because methylation is reversible, it’s hard to study DNA methylation. Although there are ways to detect DNA methylation in the lab, that science hasn’t widely transferred to patients yet.

There are some clinical tests available to detect cancer by identifying the cancer cell’s unique epigenetic markers. The company Epigenomics offers “minimally-invasive blood-based tests” that can detect either colorectal or lung cancer in the blood. Another epigenetic test, called EPICUP, can determine the type of primary tumor causing metastasis in a cancer patient.

Another company Episona has the only epigenetic fertility test available for sperm.

With the rise in popularity of genetic testing, especially direct-to-consumer kits, it’s only a matter of time before direct-to-consumer epigenetic testing kits are available.

Chelsea Weidman is a biochemist and freelance science writer/editor interested in genetics, gene editing technologies, stem cells, and novel medications. She has written for Massive and Harvard University’s Science in the News.

Her research has focused on a range of topics such as molecular imaging agents, reversible covalent chemistries, and novel antibiotic strategies. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Biochemistry and her Master of Science degree in Chemical Biology.