The apparent spike in xenophobia and tribalism that appears to be driving Brexit and a global backlash against liberal immigration policies comes amid a growing scientific consensus that humans have become more genetically alike than different over the last 50,000 years.

“Ancient populations are much more diverse than modern ones,” said Dr Eran Elhaik, a population geneticist at the University of Sheffield in England. “Their diversity was reduced over the years following events such as the Neolithic revolution and the Black Death.”

This would be of academic interest only if not for evidence that genetic diversity, or “heterozygosity” in the jargon of genetics, correlates with better fitness in many animals. While the correlation is less consistent in humans, research has shown heterozygosity can reduce our susceptibility to tuberculosis and hepatitis.

Heterozygosity occurs when we inherit two different alleles of a particular gene, or genes, from our parents. In this scenario one gene is dominant and the other recessive. Its opposite is homozygosity, in which we receive identical alleles from both our mother and father, thereby reducing genetic variation and our ability to adapt to infections and other changes in our environment.

Declining heterozygosity may seem counter intuitive given the accelerating pace of population growth, migration and admixture over the last 200 years. Yet research shows the 2 percent of our genomes that are not largely identical become more similar with time. Multiple studies, for instance, peg European ancestry of African Americans at between 10 and 50 percent.

Jet travel has only extended and accelerated this homogenization.

Founder effects

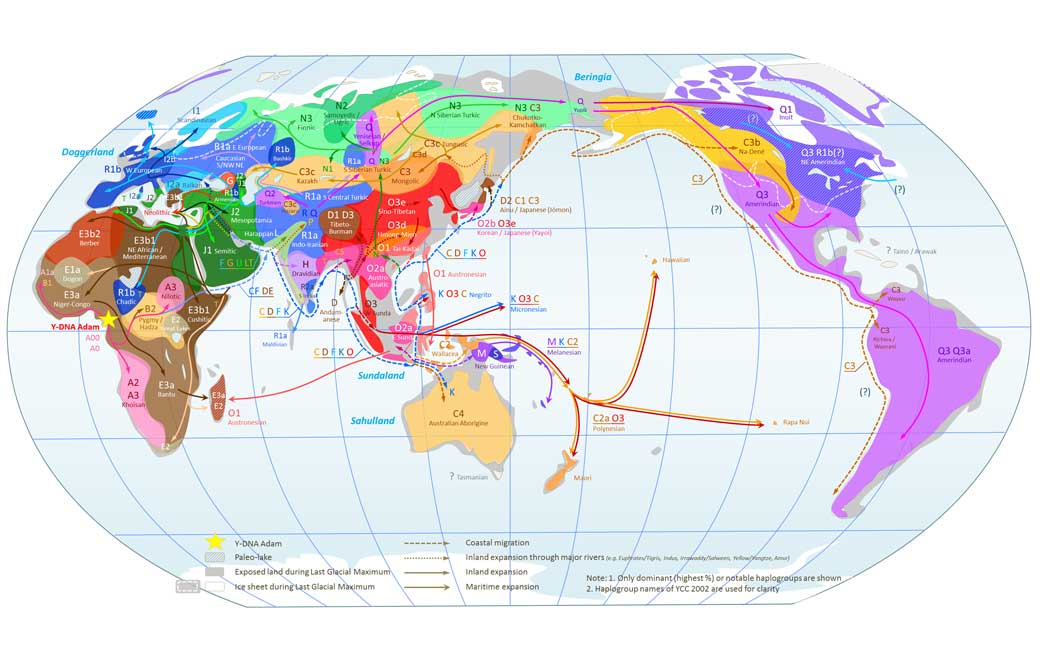

The long-held theory that human genetic diversity has been in decline throughout history was bolstered in the 1990s, when a series of studies found morphological traits and even commensal bacteria declined in ancient humans as they got further away from East Africa.

The long-held theory that human genetic diversity has been in decline throughout history was bolstered in the 1990s, when a series of studies found morphological traits and even commensal bacteria declined in ancient humans as they got further away from East Africa.

This was long thought to be the result of the “founder effect” first described by Ernst Mayr in 1942, in which the gene pool shrinks as a small number of individuals colonize new areas. Such a phenomena, researchers theorized, would mean that genetic diversity would gradually decline the further one got from East Africa.

In 2009, two British researchers set out to prove this theory and pin down when and where such events occurred. Using a program called Bottleneck, they analyzed 783 microsatellite loci previously genotyped in 53 worldwide populations to search for spikes in the ratio of heterozygosity to the number of alleles at a specific DNA location. Such sudden shifts signal sudden genetic bottlenecks.

The authors concluded their analysis provided strong support for the theory that the two most important events probably occurred about 50,000 years ago in Eurasia after a group of homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and again when an even small and more isolated group crossed from Asia to North America via the Bering land bridge about 20,000 years ago.

Disease and migration

The rise of agriculture in Eurasia around 10,000 years later led to a massive increase in human population and unhygienic living conditions that set the scene for another major genetic bottleneck: pandemics.

The rise of agriculture in Eurasia around 10,000 years later led to a massive increase in human population and unhygienic living conditions that set the scene for another major genetic bottleneck: pandemics.

It is estimated that the Black Death wiped out 30 to 50 percent of Europe’s population, or between 75-200 million people between 1347 and 1351 A.D. This would have dramatically lowered the diversity of non-recombining DNA passed along by mothers and fathers via mtDNA and Y chromosomes.

Migration likely also played a major role in reducing genetic diversity, according to studies of ancient remains found on the Iberian Peninsula. The oldest DNA recovered from the region has been traced to hunter-gatherers who appear to have migrated from other parts of Europe 19,000 years ago to escape the ice age.

An analysis of genome-wide data from 271 ancient Iberians shows they were slowly supplanted beginning around 6,000 years ago by farmers migrating from present day Turkey and North Africa, according to a study published by Science magazine in March 2019.

The authors found that around 4,500 B.C., descendants of herders from Eastern Europe and Russia began arriving. Within a few hundred years nearly all the Y chromosomes from the earlier generation had been replaced by the DNA of central European farmers.

The more we change, the more we become alike

All these factors help explain why ancient populations are much more diverse than modern ones, according to Elhaik, who is based at the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences at the University of Sheffield.

All these factors help explain why ancient populations are much more diverse than modern ones, according to Elhaik, who is based at the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences at the University of Sheffield.

“Although we have many more people today they are all far more similar to each other than ancient people,” said Elhaik, who has developed a new genetic tool he hopes direct-to-consumer DNA testing services will begin using to provide customers more precise insights into their ancient Eurasians heritage.

The testing services can’t currently do this because the commercial microarrays they use to analyze genomes are not set up to look for the genetic markers paleogeneticists have developed to classify ancient DNA. To overcome this, Elhaik’s group identified 13,000 of ancient ancestry informative markers, or aAIMs, genetic genealogy services can begin using to look for customers’ ancient ancestors. Thanks to massively parallel chips, the next-generation microarrays used by the major direct-to-consumer DNA testing services today can analyze hundreds of thousands of markers at once.

“This finding of aAIMs is like finding the fingerprints of ancient people,” Elhaik explained. “It allows testing of a small number of markers – that can be found in a commonly available array – and you can ask what part of your genome is from Roman Britons or Viking, or Chumash Indians, or ancient Israelites, etc. We can ask any question we want about these ancient people as long as someone sequenced these ancient markers. So this paper brings the field of paleogenomics to the public.”

And despite the recent backlash against immigration, many Europeans and Americans will find they have more in common with their contemporary countrymen then their ancient ancestors; at least genetically speaking.

Charlie Lunan is a science writer with a background in financial journalism who follows the intersection of genetics, evolution, infectious disease, pollution and business. In addition to his freelance work, he produces a website promoting outdoor recreation and sustainable living within a four-hour drive of his home in Charlotte, N.C.