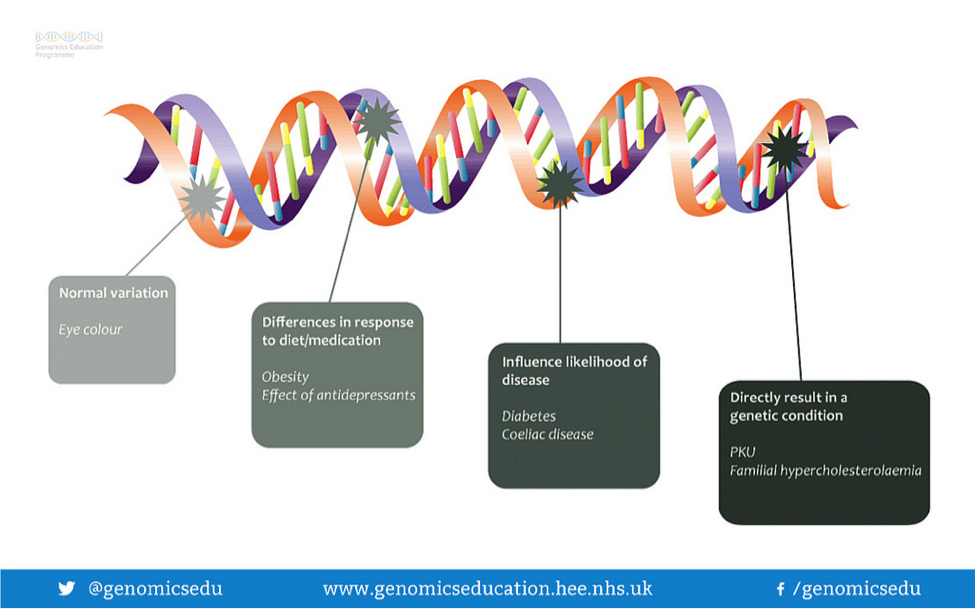

Genes. They are a piece of the complicated puzzle that separate man from animal and from one another. Made up of the DNA that is inherited from one’s parents, our genes are roadmaps and instruction manuals. They tell our cellular machinery which functional molecules to make, impacting the ingredients that make up the processes of life. Eye color, height, vision, and intellect can all be influenced by our genes.

In April 2003, the complete human genome was published by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. It marked a pivotal moment in our ability to understanding the inner workings of the human organism. As Francis Collins, Director of the National Human Genome Research Center, explains: “It’s a history book – a narrative of the journey of our species through time. It’s a shop manual, with an incredibly detailed blueprint for building every human cell. And it’s a transformative textbook of medicine, with insights that will give health care providers immense new powers to treat, prevent and cure disease.” He was right.

Before we started sequencing the human genome, scientists believed that the species Homo Sapien had between 50,000 and 140,000 genes. They had drastically overestimated. Human beings have roughly 20,500 genes, all coiled up in DNA, housed in each and every one of the trillions of cells that make you who you are. That’s 20,500 places where the machinery of human life can be altered. Many of these alterations would make life impossible.

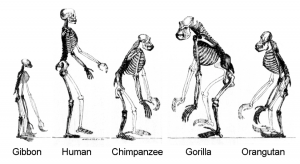

Life didn’t begin with this many genes, and our gene count varies significantly from other organisms. According to the theory of common descent, all life on earth originated from a common ancestor that lived around 3.9 billion years ago. In that time, incremental mutations in DNA have resulted in everything from wispy ocean plants through complex animal organisms like human beings.

This common history ensures that earthly DNA shares some similarities, but 3.9 billion years is also an incredibly long time. The planet’s biodiversity includes creatures that are single-celled and multicelled, propelled by legs, wings or fins, equipped with enhanced smell, hearing or even echolocation. The makeup of our DNA and the genes it comprises is equally diverse.

Scientist believe that sponges were the first animal to branch off from the tree of life, though Comb Jellies were considered for a short time. The farther back an organism breaks away from the tree, the less similar their DNA. The sponge genome contains 18,000 genes, many of which are similar to people. In fact, humans and sponges share around 70 percent of their DNA.

It gets stranger.

Since all organisms on earth share a common ancestor, the connection and commonality goes back further than the sponge. You may have heard that people share over half their genes with bananas, and this true. We all recognize, however, that people are a far cry from bananas. Half of thousands and thousands is still a large number, especially when you take into account that genes determine our form and functions as organisms. There is still plenty of room for the changes that make us so very different from plant-relatives, just as only a difference of 30 percent is enough to distinguish us from our sponge-brethren.

When comparing homo sapiens to more similar creatures, the gene-specific differences between us shrink considerably. We share about 99 percent of our DNA with chimpanzees. Though this still leaves a large number of genes that separate us, it is small enough to think about how those genes might influence our behaviors. Deciphering which genes are responsible for which attributes is a monumental task and, though we are far from solving this mystery, scientists are beginning to ask the questions.

Another factor of gene diversity is the sheer number of genes each organism has.

Though it surprises most people, human beings are not the most genetically complex animal. We may have 20,500 genes, but a teeny, tiny crustacean known as the water flea Daphnia holds the record at 31,000 genes. More than a third of this creature’s genes are unique, unknown to science until the Daphnia’s genome was sequenced in 2011

Why does such a tiny, seemingly simple creature need so many genes? Size can be deceiving, and the Daphnia is far from simple. Its aquatic environment is much more variable than ours, and it needs to adapt quickly if it wants to survive. This hypothesis fits in neatly with our data, as most of its unique genes are indeed slated to shift with environmental factors.

As project leader John Colbourne explains, “since the majority of duplicated and unknown genes are sensitive to environmental conditions, their accumulation in the genome could account for Daphnia‘s flexible responses to environmental change.”

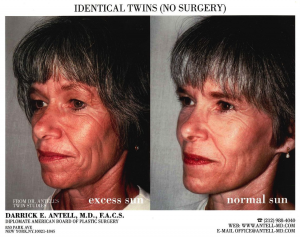

Underlying the mystery of Daphnia is epigenetics, which is the study of “changes in organisms caused by modification of gene expression rather than alteration of the genetic code itself.” Just because an organism has a particular gene, doesn’t mean it is being used. In order for genes to have an impact on an organism, they need to be read by the cell’s machinery. Any number of environmental factors can impact whether a gene is loosely waiting to be read, or coiled tightly up. At the end of the day, it isn’t only genes that matter. Epigenetics accounts for many of the differences between people. Genetically, every person in the world is 99.9 percent the same. Though some of the differences that make us unique from one another are genetics, many are epigenetic.

The exciting thing about this discovery is that they way our genes impact who we are and who we become is a fluid process – it is not set in stone. What you do can impact which genes are activated and which become, or remain, dormant. This is why identical twins, who share DNA, become more and more distinct over time. Experience matters. It really is a combination of nurture and nature, even when it comes to your genes.

Erin Wildermuth is a science writer based in Miami. She is passionate about using technology to improve human health.